The Night of Blood: Cane’s Descent into Madness and the Unveiling of a True Monster

The romantic glow of Paris was brutally extinguished, replaced by the chilling shadow of a meticulously planned massacre and a devastating act of murder. What began as a desperate, misguided attempt by Cane Ashby to reclaim his past with Lily Winters spiraled into an irreversible nightmare, exposing a layer of sinister deception that will shake Genoa City to its core. This isn’t merely a tale of love, jealousy, and betrayal; it’s the dawning of an era defined by unspeakable horror and the terrifying reveal of a puppet master lurking in plain sight.

Cane’s Obsession: A Love Corrupted by Rage

For weeks, Lily Winters and Damian had allowed their undeniable connection to flourish, moving past hushed glances to open, unashamed intimacy. They laughed in public, held hands, and kissed without fear, blissfully unaware of the storm brewing in Cane Ashby’s fractured mind. At first, Cane had tried to rationalize it, convincing himself Lily’s new relationship was just another rebound. But each time he witnessed Damian’s tender touch or heard Lily’s radiant laughter sparked by his rival, something inside Cane snapped. Pain mutated into a simmering rage, then exploded into a terrifying obsession. It was no longer about love; it was about humiliation, replacement, and a desperate struggle for control. Lily, once his, was now building a future with Damian, a future Cane believed was rightfully his. He stopped trying to win her back and began planning something far darker, something irreversible.

The Abduction and the Unthinkable Act

Lily remained terrifyingly oblivious to Cane’s descent until it was too late. Leaving a glamorous benefit gala, arm in arm with Damian, radiating the newness of their love, their world abruptly turned cold. A sharp prick in her neck, a flash of black leather gloves, Damian’s desperate shout, and then darkness. When she awoke, the air was stale, the walls concrete, and Damian lay unconscious feet away. Her screams roused him, groggy and confused, in a windowless room with a bolted steel door. Then, the lights flickered on, and Cane stepped into view, eerily calm, his eyes empty.

Lily’s initial shock morphed into chilling dread as she witnessed the wildness in his expression, the broken rhythm of his breath. This wasn’t a man pleading for a second chance; this was a man utterly unhinged. Damian attempted to reason with him, appealing to any shred of humanity Cane might have left. But Cane paced like a predator, rambling about betrayal, about being erased, about how the world would now see Lily had “chosen wrong.” His voice oscillated between ice and fire. Lily, realizing their dire situation, desperately tried to appease him, begging him to stop, telling him this wasn’t who he was. Cane’s response was a tight, joyless smile: he was finally showing them his true self.

In a desperate, final act of truth, Lily’s voice cracked as she declared her love for Damian, not as a provocation, but as an undeniable fact: “Cane, you were my past. But Damian is my heart now. Even if you kill us both, I will still die loving Damian.” The words hung in the air, a challenge, and something primal snapped within Cane. Without a word, he pulled a knife from behind his back. Damian lunged to protect Lily, but Cane was faster. With the force of all his heartbreak, jealousy, and boundless rage, he drove the blade into Damian’s chest. The sound was wet, sickening, and terribly final. Damian gasped, collapsed, and Lily’s scream shattered the silence, a guttural shriek of agony. She scrambled to his side, pressing her hands to the gushing wound, sobbing, screaming his name, but Damian’s eyes had already gone dull.

Cane stood panting, the knife dripping, his face utterly devoid of remorse. He watched Lily cradle Damian’s lifeless body, her hands trembling, her mouth quivering, her soul visibly breaking. Then, as if waking from a nightmare, Lily looked up at him, her voice cutting deeper than any blade: “You’re a monster. You’re not a victim. I will never forgive you. And I swear, I will make you pay.” Cane recoiled, sudden uncertainty in his eyes. The enormity of his act began to sink in; he had crossed a threshold from which there was no return. He fled, locking Lily inside with the body of the man she loved. For agonizing hours, she screamed, battered the door, and wept over Damian’s corpse, until authorities, alerted by a twisted tip from Cane himself, finally rescued her. Dehydrated, bloodstained, and in shock, Lily uttered only three words: “He killed him.”

Justice, Trauma, and a Chilling Disappearance

The trial that followed was swift, brutal, and public. Cane Ashby, once respected, became a cautionary tale of obsession turned deadly. Lily testified, her voice hollow, her eyes distant, her soul fractured. Amanda Sinclair, now representing the state, delivered a clinical, lethal cross-examination of Cane. Devon Hamilton sat silently in the gallery, watching the destruction unfold. The sentence: life in prison without parole. But for Lily, no punishment could ever bring Damian back. In the weeks that followed, she withdrew from the world, leaving Genoa City to grieve in isolation, severing all ties. Damian’s funeral was small, private, a silent testament to a life tragically cut short.

Cane, meanwhile, rotted behind bars, consumed by the ghosts he had created. Lily haunted his dreams, no longer the woman who loved him, but the woman whose life he had shattered. Damian’s hollow, accusing eyes stared back at him nightly. Some acts damn a man forever; some lines, once crossed, can never be undone. For Cane, love was never enough to save him; it was the weapon that destroyed everything.

The Ultimate Twist: Cane Was Only a Puppet!

But even as Genoa City mourned, and the authorities pinned everything on Cane’s jealous rage, Devon Hamilton couldn’t shake a chilling premonition. He knew Cane too long, too deeply, to believe this was a simple act of impulse. Replaying the Paris events, Devon began to see not chaos, but choreography. Cane’s behavior, the timing, the very setting of the “gala”—it all felt like a diversion. What if Cane hadn’t just wanted to punish Lily and Damian? What if that was merely the visible tip of a much larger, darker operation? What if every guest in that ballroom had been handpicked, not for their connection to Cane, but for their relevance to someone else entirely?

Devon’s suspicions deepened when he confronted Amanda. Her sharp, calculated refusal to confirm or deny anything, almost rehearsed, told him everything. Amanda wasn’t just a bystander; she was either deeply involved or had uncovered something so dangerous she couldn’t speak. If so, then the real threat wasn’t Cane. It was whoever Cane was working for, or pretending to be. The name Aristotle Dumas had been a whispered ghost story among billionaires, appearing only in rumors and coded transfers. But now, Devon couldn’t ignore how often Cane’s name had been intertwined with Dumas’s signature deals. What if Cane wasn’t Dumas, but merely the mask he wore? What if the world had been watching the wrong man all along?

The Real Dumas Revealed: A Shadow in Plain Sight

It was then that Devon’s focus shifted to Holden Novak, a charming, unassuming businessman who had attended the Paris Gala and conveniently disappeared just before the chaos erupted. Devon despised coincidences. As he dug deeper, he found patterns: Holden’s financial interests aligning too often with projects linked to Cane—or rather, to Dumas—transactions in Nice shell companies, confidential meetings in Vienna, and a web of communication tracing back to encrypted military-grade networks. The horrifying realization hit him like a freight train: Holden wasn’t a guest; he was a handler, a liaison, still working under Aristotle Dumas, or worse, still working under the real Dumas while Cane played the fool.

The implications were staggering. If Cane had never truly been Dumas, then the entire Paris event—the murder, the panic, the lockdown—had been a calculated act of misdirection. While everyone was consumed by the bloodshed, by Lily’s screams and Damian’s death, something else, something far bigger, had been executed elsewhere. Amanda remained tight-lipped, but Devon saw the panic flicker in her eyes every time Dumas’s name was spoken. He noticed her evasiveness when he mentioned Holden. And when Devon confronted her about Cane’s supposed confinement in Nice, how Cane had told everyone he couldn’t leave the estate, how he’d insisted they were all trapped, Amanda didn’t even bother to deny the lie. The fact that Cane reappeared in Genoa City the following week proved he had always had the means to leave, meaning the guests in Paris weren’t trapped by circumstance; they were intentionally detained, held in place while the true objective—a transfer, a document signed, a life erased, perhaps even a government infiltrated—was accomplished. The bloodshed had served its purpose: to mask the real crime, to keep eyes off the true objective. And now, Cane was either in hiding or, more likely, had been disposed of by the very man he impersonated.

In Genoa City, the atmosphere shifted dramatically. Amanda became reclusive, disappearing for days. Holden returned from abroad, his stories inconsistent, his alibis full of holes. The press fixated on the Paris tragedy, but Devon focused on the silence that followed. Someone powerful wanted the world to believe the horror had ended with Cane’s breakdown. But Devon knew better. He felt it in his bones: the true orchestrator had yet to show his face. And so, while the city mourned, while Lily healed in isolation, and the media devoured every whisper of the story, Devon began building his own network, quietly, methodically, reaching out to allies and hiring ghost-tracking investigators. He knew that if they were to survive whatever came next, he had to expose the truth, however dangerous. Because if Dumas was real, and Cane had been merely the illusion, then the real nightmare wasn’t Paris. It was what came after.

The 15 Greatest Supercars of the Last 100 Years Are Parked at the Petersen

11

1988 Porsche 959S

Petersen Automotive Museum

The 959 was revolutionary not because of its engine power – 444 hp – or aerodynamics – 0.31 cD – but because it sent varying amounts of torque to all four wheels via a semi-complex torque-biasing all-wheel-drive system. That system would be seen in a million Porsches down the road and eventually become almost commonplace, but for 1986 it was otherwordly.

12

1989 RUF Porsche CTR Yellowbird

Petersen Automotive Museum

This was once not only the fastest car in the world, achieving over 200 mph. But in hitting that speed it surpassed the then-revolutionary Porsche 959, which had gone 198. Alois Ruf, in his relatively small shop and with limited resources, retuned the five-speed transmission, lightened his car and redesigned the aerodynamics, the result being a remarkable 213 mph on Italy’s Nardo test track. It was the first production-based car to break 200 mph. RUF still makes cars and they still go very fast.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

13

1991 Acura NSX

Petersen Automotive Museum

The Acura NSX is remembered not just for being the first Japanese supercar, but for also being remarkably fun and easy to drive fast. The V6-powered NSX was aimed at beating the performance and handling of the Ferrari 328, the top dog in the class. The steering feel was the most amazing thing about the car, it felt, as one great writer said at the time, like you were sitting on the front axle with a tie rod in each hand.

14

1992 Jaguar XJ220

Petersen Automotive Museum

In the late-’80s Tom Walkinshaw Racing was winning Group C sports car races across Europe. So Jag decided to capitalize off that by having TWR build this. Jaguar made 282 of these long beautiful coupes between 1992 and 1994, and you could argue that at the time it was the fastest production supercar ever made. Not only did it hit 212 mph on the Nardo test track, but it lapped the Nurburgring in 7:46. Remember, this was before Nurburgring lap times for production cars were really a thing, but still, that was pretty good for almost 30 years ago. Unfortunately, the early-’90s recession dried up demand for the car and production ended in 1994.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

15

2003 Saleen S7

Petersen Automotive Museum

Brilliantly fast around a race track, the Saleen S7 was less satisfying on regular roads. The concept was good, a mid-engine V8 in a steel and aluminum frame wrapped in carbon fiber body panels. The S7 saw success in various racing series around the world.

16

2003 Maserati MC12

Petersen Automotive Museum

The limited-edition Maserati MC12 marked the company’s return to racing after 37 years away. It rode on the same chassis as the Ferrari Enzo, and was powered by the Enzo’s 6.0-liter V12 making 624 hp. Top speed was 205 mph. Only 50 road cars were ever produced, all for homologation purposes, while 12 race cars were made. The last time one sold at auction appears to be 2016, when it hammered at $1,430,000. So they would have been a good investment, especially if you drove them occasionally.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

17

Ferrari 288 GTO

Petersen Automotive Museum

Another great race car that had to be offered for sale to the public for homologation purposes. For it to race in the FIA Groupe B category, Maranello had to produce 200 street versions of the 288 GTO. Unfortunately, Group B was cancelled, so the car never got a chance to race. Ferrari sold the customer cars anyway. They were powered by a 400-hp V8 mounted longitudinally instead of transversely. Doors, trunk and deck lid were aluminum, while glass reinforced plastic and carbon composites make up the rest of the body, a pre-cursor to the carbon fiber to come in car design.

18

1991 Ferrari F40

Petersen Automotive Museum

The F40 was the ultimate poster boy supercar when it came out in 1987. With a twin-turbo V8 making 478 hp in a Pininfarina-designed body, the whole thing weighed just 3000 lbs. It was Enzo’s last car, too, so he wanted it to be speciale. Indeed it was, distinct in every way from the 288 GTO before it and from the F50 that came after. Sure there was turbo lag, but all you had to do was keep the revs up. While the original sticker was $400,000, they almost always clear a million, sometimes two, at auctions.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

19

1969 McLaren M6GT

Petersen Automotive Museum

This was McLaren’s first attempt to take its tremendous success on the track and transfer it to the street. Bruce McLaren’s goal with the M6GT was nothing less than to have the fastest and quickest road car in the world. He already had the best race cars. Top speed was going to be 165 mph and 0-100 was going to take eight seconds. Then, sadly, Bruce McLaren was killed in a testing accident at Goodwood in 1970 and the project was shelved. It wasn’t until 25 years later, when Gordon Murray, working for McLaren, penned the F1, and 13 years after that when we got the MP4-12C, which launched the string of McLaren road cars we all enjoy today.

20

Lamborghini Countach

Petersen Automotive Museum

Why did the Lamborghini Countach drive everybody crazy with lust for the 25 years of its production run? It wasn’t because it was a great driver. Heck, you could barely see out of the thing. And it wasn’t a great handler. Not that any of the lusters would ever know. It was just that the Countach seemed to represent something none of us would ever have: power, prestige, &%$$^! The ultimate poster car, the Countach was Marcelo Gandini’s most-revered design for many years. Even now it can conjure great memories of la dolce vida we all imagined.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

21

1967 Ford GT40 MkIII

Petersen Automotive Museum

Another race car for the street, the Ford GT40 was built for one purpose and one purpose only, to beat Ferrari at Le Mans. And the GT40 did it, as anyone who saw that movie now knows. The first GT40 started life as a Lola, then went on to meld into what you see here, which is a later development of the original race car. That big V8 engine right behind your head makes you think of Dan Gurney and AJ Foyt at Le Mans, or Bruce McLaren, or pick your favorite driver from that era, chances are he will have driven a GT40 at some point. This model was a rare street version of the MkIII, once owned by the great conductor Herbert von Karajan. Now, with Ford GTs practically flooding the marketplace, anyone with a half a million bucks can afford to play Le Mans racer, and have terrific fun doing it.

22

1967 AC Shelby Cobra 427

Petersen Automotive Museum

Speaking of legends, is there any character more beloved by Autoweek readers than Carroll Shelby? Sure, he was no saint, but you could forgive some sinners if they were as charming as old Shel’… and if they won. The Cobra was a brilliant idea by Shelby, put a big American V8 into a tiny AC British sports car and voila, you’re winning your class at Le Mans. The Cobra is not a delicate handler, light to the touch and perfectly balanced. It is a brute at full throttle, and goes from understeer to oversteer faster than you can make a deal with the gods of lateral acceleration. But it remains wildly popular among owners and lusters alike. You can even get a continuation car for what may be a reasonable price.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

23

1959 Ferrari 250 GT LWB Berlinetta

Petersen Automotive Museum

This prototype was built to bridge the gap between the Tour de France models and the coming and far more famous SWB, or Short Wheel Base, 250s. With 240 hp from a 3.0-liter V12, it had a top speed of 157 mph.

24

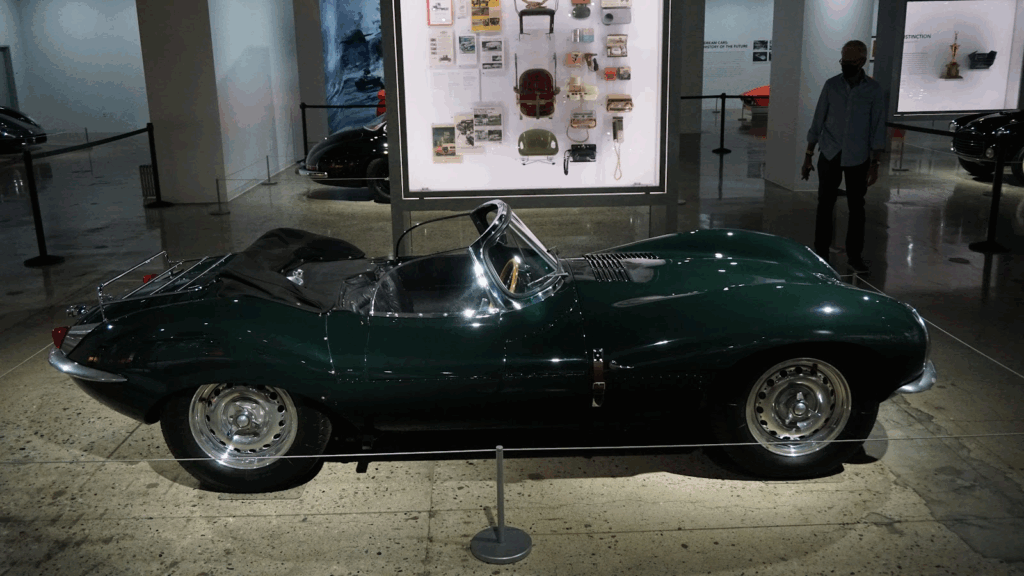

Jaguar XKSS

Mark Vaughn

While anything touched by Steve McQueen is immediately made cool, imagine how cool it would be to drive this XKSS once owned by The King of Cool himself? The Petersen Museum has had this car for several years, and staff members can even be seen exercising it on city streets around the museum. All of the original XKSS started life as racing D-Types that were converted to street use with minimal changes. So while this car’s provenance is unmatched, its performance is equally pure. Only 25 of these were ever made, including nine made in recent years to replace models lost in a fire at the factory. It remains one of the great supercars of the 20th century.

Advertisement – Continue Reading Below

25

Bugatti EB110

Mark Vaughn

It was the late-80s/early ’90s and Bugatti was back, baby! The storied marque was revived by Italian entrepreneur Romano Artioli, who seemed to do it on the strength of his personality alone. When the EB110 debuted at Versailles and Paris in 1991 it had a massive, 60-valve V12 with four, count ’em, four turbochargers. It made 553 hp and was said to be a superb driver. Derek Hill even piloted one at Daytona in 1996. But Artioli overreached when he sought to acquire Lotus and that, combined with a recession, sent the Bugatti name back on on hiatus after only 139 EB110s were made.

26

2008 Bugatti Veyron 16.4

Mark Vaughn

Then in 1998, under the iron glove of megalomaniac VW ceo Ferdinand Piech, Bugatti came back and has since stayed back. The Veyron was its first product and the Veyron 16.4 was its supercar among supercars. The Veyron 16.4 was the fastest production car in the world when it came out, hitting 253 mph. It’s 8.0-liter W16 engine made an absurd 986 hp, which is 1000 metric hp. Only 450 were ever built. But they’re still making versions of the Veyron’s successor, the Chiron, so buy all you want, they’ll make more. Just bring $3 million dollars. Financing available.